|

BARIANTIQUA BariAntiquA nasce a Bari, nel 2016, unendo le professionalità e le diverse esperienze di due generazioni di musicisti, con la volontà di intraprendere un percorso artistico finalizzato a valorizzare il patrimonio culturale e musicale del territorio pugliese. Incontratisi grazie ad una felice intuizione di EstevanVelardi, hanno scelto di fondare i loro progetti su solide basi storico-musicologiche ed utilizzare strumenti musicali appropriati al repertorio proposto, valorizzando, quando possibile, opere organarie del patrimonio pugliese. Al loro primo lavoro, le sonate di Pietro Migali, Maestro di Cappella della Cattedrale di Lecce, in prima registrazione ed esecuzione, seguirà un progetto sulle musiche conservate negli archivi dei conventi pugliesi delle benedettine, una ricerca connessa ai rapporti musicali e commerciali dell’olio verso altre regioni italiane ed europee durante il xvii secolo, ed un lavoro sui viaggi del cartografo PīrīReʾīs, ammiraglio navale ottomano, che preparò numerosi disegni delle principali città della Puglia e del resto del bacino del Mediterraneo.

BARIANTIQUA The idea of founding BariAntiquA was Having met thanks to Estévan Velardi’s perceptive insight, the ensemble founds its projects on a solid historical-musicological basis, and performs on instruments appropriate to the proposed repertoire; to this end, organs of the Apulian heritage are used whenever possible.

|

Pietro Migali Sonate a tre, due violini, e violone, ò arcileuto, col basso per l'organo op.I

MVC/017-044 DDD

Prima registrazione mondiale -First recording Sonate I - XII

BARIANTIQUA

Testi libretto

- Booklet texts |

|

|

|

|

Pietro Migali da Lecce

Sonate a tre, due violini, e violone, ò arcileuto, col basso per l'organo op.I di Diego Cantalupi Nel 1871, anno dell’inaugurazione del teatro Paisiello di Lecce, Sigismondo Castromediano, patriota, archeologo e letterato italiano, scriveva che «diverse composizioni sacre e profane in musica ed in prosa manoscritte si conservano da certi amatori». Le poche notizie biografiche su Pietro Migali ci vengono tramandate dal testamento dello stesso Migali, conservato presso l’Archivio di Stato di Lecce: rimasto orfano del padre Angelo “d’anni 22 incirca” (ma vedremo tra poco come questo dato vada rettificato), si prese a carico l’intera famiglia composta dalla madre, Francesca Redesi, e da sette fratelli. Il testamento fu redatto il 6 settembre 1715 e questo giorno rappresenta il terminus post quem che certifica il compositore ancora in vita; suo padre morì nel 1669 e se fosse vero che Migali era ventiduenne sarebbe dovuto essere nato attorno al 1647. Tuttavia, l’atto di battesimo conservato presso il Duomo di Lecce , datato 6 gennaio 1635, crea una discrepanza di ben 12 anni rispetto alla data riportata nel testamento. Non stupisce che un Migali ottantenne, e magari sul letto di morte, avesse scarsa memoria degli avvenimenti accaduti mezzo secolo prima; questo dato però, risulterà particolarmente importante per incrociare alcune tappe della vita del nostro compositore con quelle di Arcangelo Corelli. In tutti i documenti, Pietro Migali è menzionato come clerico. Clerico o chierico non identificava il sacerdote, ma colui che, pur non avendo ricevuto gli Ordini maggiori (suddiaconato, diaconato e presbiterato), era entrato a far parte del clero, garantendosi la rendita di un beneficio ecclesiastico; i clerici potevano attendere a qualsiasi professione e potevano anche sposarsi (ma una sola volta, e con una vergine). La rendita permetteva di potersi dedicare interamente alla loro vocazione intellettuale senza dover continuamente cercare un sostegno economico. Non abbiamo notizie circa la formazione musicale di Pietro Migali; non sono pervenuti documenti né altre informazioni che possano far chiarezza su questo periodo della sua vita. Sappiamo che fu frequentatore assiduo della casa di Diego Personè, «eminente nella tastatura degli organi, nella Musica, nella Scherma, e nelle arti militari, ma di maniera»; da Diego e dal figlio Camillo, anch’egli ‘musico’, avrebbe ricevuto protezione e magari anche ‘istruzione’. La raccolta di sonate pervenutaci testimonia capacità compositive di alto livello, un unicum nel panorama pugliese del Seicento. Difficilmente l’istruzione musicale di Migali fu ristretta all’ambito cittadino, quasi certamente si estese in ambito napoletano o più probabilmente romano.

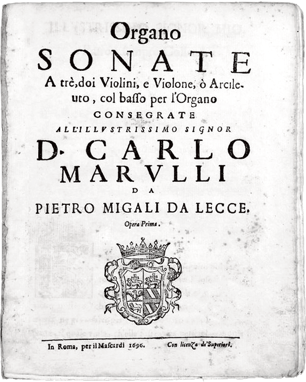

D’altra parte se si prese cura della famiglia alla morte del padre, cioè a 35 anni, a quell’età doveva già essere un musicista formato e affermato, e avrebbe dovuto avere tempo sufficiente per un periodo di studio in uno dei centri musicali più importanti dell’Italia centro-meridionale. L’op. I è dedicata D. Carlo Marulli, sacerdote barlettano, di famiglia nobile. Nel frontespizio compare lo stemma nobiliare del casato, e all’interno di ciascuno dei quattro libri parte, una dedica dalla quale traspare una buona cultura e una discreta padronanza della lingua italiana. La raccolta di Sonate a tre venne pubblicata a Roma nel 1696 (la dedica riporta: Lecce, 12 febbraio 1696), quando Migali aveva 61 anni circa; sicuramente rappresenta il lavoro di un musicista maturo, ottimo conoscitore dello stile ‘romano’ della fine del Seicento. Ipotizzando che Migali fosse a Roma attorno ai suoi vent’anni, cioè all’incirca nel 1655, difficilmente avrebbe potuto incontrare Corelli, dato che la sua presenza nella Città eterna è attestata solo dal 1675 e in quell’epoca un compositore di quarant’anni come Migali doveva essere già affermato e conosciuto. La musicologia ha negli ultimi anni individuato e definito uno stile romano della musica strumentale, di cui Corelli sarebbe il più alto rappresentante: « il musicista romagnolo riesce a proporre all’Europa un nuovo modello formale puro, equilibrato, ricco di distillata sostanza musicale, e nel contempo a proseguire idealmente la linea stilistica romana, facendo proprie ed incorporando nel senso stretto del termine importanti invenzioni dei suoi illustri predecessori, fra tutti Alessandro Stradella» , sostiene il violinista Enrico Gatti. In questa ‘linea stilistica romana’ si potrebbe inserire quindi l’attività di Migali, seppure questa mia idea non supportata al momento da alcun documento. C’è tuttavia un altro indizio che potrebbe mettere in relazione il nostro compositore all’ambiente romano precorelliano: tra i compositori attivi a Roma nel terzo quarto del Seicento particolare importanza rappresenta la figura di Carlo Mannelli ‘del violino’: di cinque anni più vecchio di Migali, nacque, visse e operò a Roma, prima come cantore, poi come violinista. Nel 1682 pubblica per i tipi di Angelo Muti a Roma la sua seconda raccolta di sonate (Sonate a tre, due violini, e leuto ò violone, con il basso per l’organo). Questa raccolta è l’unica a riportare indicazioni sull’uso dell’arco, attraverso l’utilizzo di alcuni segni, ancora oggi di dubbia interpretazione; alcuni simboli simili compaiono anche nella raccolta di Migali, che potrebbe essere stata concepita e/o composta proprio in quegli anni, durante un probabile, anche se non dimostrabile, soggiorno romano.

Note interpretative di Diego Cantalupi Gli strumenti indicati sul frontespizio dei quattro libri-parte non lasciano adito a dubbi circa la destinazione di queste sonate: si tratta di sonate ‘da chiesa’ per due violini e basso continuo, composte per l’organico tipico della trio sonata secentesca. Se l’organo, in qualità di strumento da tasto, non fa altro che confermare la destinazione ‘sacra’ di questi lavori, è necessario fare alcune considerazioni sull’indicazione relativa allo strumento che compare nel libro-parte destinato al Violone, ò Arcileuto. Premesso che le differenze, a livello di contenuto, sono minime e la linea di basso del violone si differenzia da quella dell’organo per pochissimi dettagli, si è qui scelto di utilizzare un arciliuto (oltre a una tiorba), principalmente per ragioni di equilibrio sonoro: laddove l’organo può tenere note lunghe, lo strumento a pizzico garantisce maggior dettaglio nei passaggi veloci. Il violone, strumento alla fine del Seicento ancora morfologicamente e timbricamente diverso dal violoncello che oggi conosciamo, viene dato come strumento alternativo, e ciò è anche confermato dalla presenza di soli quattro (e non cinque) libri parte. Per la presente registrazione è stata preparata un’edizione critica a cura di Diego Cantalupi e Edward Szost, basata sui due esemplari completi ad oggi noti delle Sonate di Migali. Essi sono conservati presso la Biblioteca del Conservatorio di Bologna (oggi noto come Museo internazionale e Biblioteca della Musica) e presso il Fondo Santini della Diözesanbibliothek di Münster. La registrazione è stata effettuata utilizzando l’organo posto nella Cappella della Madonna della Madia, presso la Cattedrale di Monopoli. Lo strumento, anonimo, è stato costruito nel xvii secolo ed è stato parzialmente modificato nel 1762 da Pietro De Simone jr. Il temperamento è mesotonico modificato, con un la corista di 436, 7 Hz a 23°C, e una pressione del vento di 42 mm in colonna d’acqua.

|

Pietro Migali da Lecce

Sonate a tre, due violini, e violone, ò arcileuto, col basso per l'organo op.I by Diego Cantalupi In 1871, the year the Paisiello Theatre in Lecce was inaugurated, Sigismondo Castromediano – patriot, archaeologist and scholar – wrote that "several manuscripts of sacred and secular compositions in music and prose are preserved by some amateurs." Given that no evidence exists to confirm the statement, we admit that the musical scene in seventeenth century Lecce must have been bleak.Three librettos of oratorios have survived (but without their music)as have a few books of madrigals.In this context, the importance and beauty of Pietro Migali’s sonatas represent something unique in the region. The works are also a useful starting point to reconstruct the musical environment of the city in the late seventeenth century. What little information we have concerning Pietro Migali comes from his will, kept at the State Archives of Lecce. That document states that he was “about 22” when his father Angelo died (but we willshortly see that this date should be corrected). He took charge of the entire family, including his mother, Francesca Redesi, and his seven siblings. The will is dated 6 September 1715 and represents the terminus post quem, proof that he was still alive on this date. His father died in 1669, and if it were true that Migali was 22 at the time,his date of birth would be placed at around 1647.However, the act of baptism kept at the Cathedral of Lecce is dated 6 January 1635, a discrepancy of 12 years from the date indicated in his will.It is not surprising that Migali, at eighty and perhaps on his deathbed,had little memory of the events that had taken place half a century earlier. This detail, however, will be used to cross-reference certain stages of his life with those of Arcangelo Corelli. In all the existing documents, Pietro Migali is mentioned as a "cleric." Clerics or canons were not priests, but despite not having received the Major Orders (sub-diaconate, diaconate and presbyterate), they were members of the clergy and were thus guaranteed an income of an ecclesiastical benefice. The rules stipulated that clerics could be of any profession and could even get married (but only once, and with a virgin). The annuity allowed them to devote themselves entirely to their intellectual vocation without having to constantly worry about their livelihood. We have no information regarding Migali’s musical education; documents or other information that could shed light on this period of his life have not been uncovered.We know that he was an assiduous visitor at the house of Diego Personè, whowas "a fine organist and accomplished in music, in fencing, and in the military arts, but manneristic”. Migali may have received protection and maybe even ‘instruction' from Diego and his son Camillo, also a 'musician'. This collection of sonatas attests to Migali’shigh level of compositional skills, unique in the musical scene of seventeenth century Apulia. It is unlikely that his musical education was limited to his native city; it almost certainly extended to Naples or more probably to Rome.

Nevertheless, if he was able to support the family after the death of his father, he must have already been a trained and accomplished musician; furthermore, he would have had the opportunity to study in one of the important musical centres in central-southern Italy.His "lucrative profession of Maestro di Cappella and Music Composer” is confirmed by his only surviving printed work. We have no other information regarding other compositionsor manuscripts. Op. I is dedicated to D. Carlo Marullo, a priest from a noble family in Barletta, whose family’s coat of arms appears on the title page. Each of the four partbooks that make up the work contains an inscription that reveals Migali’s excellent command of the Italian language.The collection of three sonatas was published in Rome in 1696 (the inscription reads: Lecce, 12 February 1696), when the composer was roughly 61. It represents the work of a mature musician with considerable knowledge of the 'Roman' style of the late seventeenth century. Assuming Migali was in Rome when he was around 23, i.e. in approximately 1655, a meeting with Corelli would have been unlikely given that the presence of the latter in the city is attested only from 1675; moreover, in that period the 40-year-old Migali would have already been well-known and established. In recent years, musicologists have identified and defined a Roman style of instrumental music, and Corelli was its greatest representative. The violinist Enrico Gatti comments that "Corelli offered a new formal model, which was pure, balanced, and full of musical substance; at the same time he continued the Roman stylistic line, endorsing and incorporating the significant inventions of his illustrious predecessors, among them Alessandro Stradella.”The works of Migali could be inserted into this 'Roman style', although this idea is not supported by any evidence. But there is another factor that could place our composer in Rome in a pre-Corellian period. Among the composers active in Rome in the third quarter of the seventeenth century, Carlo Mannelli, also known asCarlo del violin, was one of the most important. Five years older than Migali, he was born in Rome and lived and worked there, first as a singer, then as a violinist. In 1682,his second collection of sonatas (Sonate a tre, two violins and lute or violone, with the bass continuo for organ) was published by Angelo Muti in Rome. This is the only collection that contains indications on bowing, represented with certain markings with a dubious interpretation even today.Some similar markings appear in Migali’s collection, which may have been composed in those years, during a possible though not verifiable sojourn in Rome.

Performance notes by Diego Cantalupi The instruments shown on the title page of the four partbooks leave no room for doubt regarding the destination of these 'da chiesa' sonatas for two violins and basso continuo, composed for the typical instrumentation of the seventeenth century trio sonata.While the presence of the organ confirms the 'sacred' nature of these works, we should consider some of the indications in the partbook intended for the violone or archlute. Given that the differences, in terms of content, are minimal and that only minor details distinguish the bass line of the violone from that of the organ, an archlute was chosen (in addition to a theorbo)mainly due to sound balance: whereas the organ may hold long notes, plucked instruments provide greater detail in fast passages.In the late seventeenth century, the violone was morphologically and tonally different from the present day cello. It was indicated as an alternative instrument, and this role is also confirmed by the presence of only four (and not five) partbooks. For this recording, a critical edition was edited by Diego Cantalupi and Edward Szost, based on two complete works, nowknown as the Sonatas of Migali. These are kept in the library of the Bologna Conservatory (known as the International Museum and Library of Music) and in the Santini Collection in the Diözesanbibliothek in Münster.The recording was made using the organ in the Chapel of Our Lady of the Madia in the Monopoli Cathedral. The anonymous seventeenth century instrument was partially modified in 1762 by Pietro De Simone Jr.The temperament is a modified meantone with a pitch of 436.7 Hz at 23°C, and a wind pressure of 42mm in a water column.

|

|