|

contenuto musicale - contents: Niccolò Paganini SONATE M.S. 84 CD 1 Sonata 1. Minuetto-Andantino [1’57’’] Sonata 2. Minuetto-Allegretto ossia Rondoncino [2’43’’] Sonata 3. Minuetto-Valtz [1’57’’] Sonata 4. Minuetto-Rondoncino [3’44’’] Sonata 5. Minuetto-Andantino [3’25’’] Sonata 6. Minuetto-Allegretto [2’32’’] Sonata 7. Minuetto-Valtz [1’58’’] Sonata 8. Minuetto-Allegretto scherzando [2’22’’] Sonata 9. Minuetto-Valtz [3’24’’] Sonata 10. Minuetto-Valtz [2’31’’] Sonata 11. Minuetto [2’20’’] Sonata 12. Minuetto-Allegretto [2’47’’] Sonata 13. Minuetto-Andantino [3’21’’] Sonata 14. Minuetto-Valtz [3’46’’] Sonata 15. Minuetto-Perligordino [4’09’’] Sonata 16. Minuetto-Allegretto [3’45’’] Sonata 17. Minuetto-Perligordino [2’46’’] Sonata 18. Minuetto-Allegretto [2’30’’] Sonata 19. Minuetto-Allegretto [2’20’’] Sonata 20. Minuetto-Valtz [1’52’’] Sonata 21. Minuetto-Valtz [2’17’’] Sonata 22. Minuetto-Andantino [2’28’’]

CD 2 Sonata 24. Minuetto-Andantino [2’54’’] Sonata 25. Minuetto-Valtz [3’37’’] Sonata 26. Minuetto per la Signora Marina-Allegretto [1’58’’] Sonata 27. Minuetto per la Signora Marina-Valtz [1’57’’] Sonata 28. Minuetto-Andantino Amoroso [3’18’’] Sonata 29. Minuetto-Andantino [3’41’’] Sonata 30. Minuetto-Allegro [2’56’’] Sonata 31. Minuetto-Rondoncino-Valtz [2’50’’] Sonata 32. Minuetto-Valtz [2’51’’] Sonata 33. Minuetto Minore-Andantino [4’20’’] Sonata 34. Minuetto Umigliato alla Gentilissima Signora Emiglia Denegri [1’40’’] Sonata 35. Minuetto [2’56’’] Sonata 36. Minuetto [2’29’’] Sonata 37. Minuetto [1’52’’]

SONATE M.S. 85 Sonatina 1. Allegro [2’51’’] Sonatina 2. Marcia-Corrente Passo doppio [3’01’’] Sonatina 3. Andante [2’03’’] Sonatina 4. [Allegro] [4’58’’] Sonatina 5. [Allegretto]-Allegretto [4’49’’]

SONATE M.S. 85 Sonata Minuetto-Rondò allegro [4’34’’] |

-

Nicolò Paganini -

2CDs

Massimiliano Filippini

Testi libretto

- Booklet texts |

|

|

|

Massimiliano Filippini chitarra- Guitar

Guitarist and composer, was born in 1975 in Desenzano del Garda. |

Paganini e la chitarra Niccolò Paganini (Genova, 1782 - Nizza, 1840) è universalmente riconosciuto come il più grande virtuoso del violino e innovatore della tecnica violinistica. In tempi recenti gli studi si sono concentrati sull’analisi delle sue numerose composizioni con l’intento sia di contestualizzare il suo stile musicale nell’ambito della propria epoca sia di rivalutare la sua figura di compositore, troppo spesso offuscata dalla sua stessa fama di virtuosoo relegata frettolosamente dai critici come finalizzata al mero sfoggio di bravura strumentale. Analizzando la produzione Paganiniana nel suo complesso ci si rende conto di quanto sia presente la chitarra, non solo come strumento di accompagnamento nelle sonate per violino, nei trii e nei quartetti ma anche come strumento solista. Anche le fonti ci rivelano che Paganini, oltre che ad essere stato lo straordinario ed eccentrico violinista virtuoso capace di entusiasmare il pubblico della prima metà dell’800 in Italia e in Europa, è stato anche un abilissimo chitarrista, anche se le sue performance con questo strumento sono avvenute solo nell’ambito privato; non abbiamo infatti testimonianze di sue esecuzioni pubbliche con la chitarra. È Paganini stesso nella sua Autobiografia a raccontare del suo rapporto con gli strumenti a pizzico che avvenne in tenerissima età: “Con cinque anni e mezzo imparai il mandolino da mio padre, […] In età di 17 anni feci un giro nell’alta Italia ed in Toscana, […]. Restituitomi in patria, mi dedicai all’agricoltura, e per qualche anno presi gusto a pizzicare la chitarra”. Ben presto inizia anche a comporre per la chitarra, come egli stesso racconta al suo biografo Maximilian Schottky: “Per un periodo piuttosto lungo ho fatto la spola tra Parma e Genova, dove feci il dilettante più che il virtuoso; infattisuonai molto ma perlopiù in circoli privati. Con molta diligenza mi dedicai allacomposizione e scrissi anche molto per la chitarra.” Siamo dunque attorno agli anni 1795-1796 quando Paganini comincia a interessarsi alla chitarra e da allora al 1804 comporrà il corpus principale delle sue opere per chitarra costituito dalle 37 sonate per chitarra (M.S. 84), le 5 sonatine (M.S. 85) che sono l’oggetto della presente registrazione. “Pregai Paganini di venire a colazione da me la mattina successiva poiché volevo suonargli qualcosa. Preparai il violino e tre pezzi molto difficili e per di più manoscritti. Mentre accordavo il violino egli sfogliava la musica di uno studio, accennando la con le dita su di un bicchiere di champagne di cui aveva assaggiato soltanto una metà. “È molto difficile”. Esclamò. Improvvisò in un batter d’occhio un leggio con un cappello e il bicchiere che si trovava già sul tavolo e vi appoggiò la mia musica. La prima parte del mio studio mi riuscì quel giorno meglio che mai. Avevo appena cominciato il ritornello quando Paganini, che leggeva la musica con me, ebbe uno scatto e uscì dalla camera senza dire una parola. Restai di stucco. […] Ma un attimo dopo il Maestro rientrò con una chitarra in mano. […] Paganini accordò la chitarra. Stupito gli chiesi che cosa significasse tutto quel armeggio. Egli si mise a ridere, si sedette accanto a me e mi pregò di riattaccare lo studio che mi avrebbe accompagnato, venendone avvantaggiata la composizione. Io ero estremamente curioso, in primo luogo perché non sapevo che Paganini suonasse la chitarra, padroneggiandola come il violino, in secondo luogo perché dubitavo che ‘a prima vista’ gli riuscisse di afferrare la base armonica della mia composizione. Se il giorno prima avevo ammirato Paganini come il primo violinista del mondo, ora provavo per lui una sconfinata ammirazione come virtuoso di chitarra e per l’enorme talento dimostrato nel rendere lo spirito della mia composizione e nell’improvvisare un così stupendo accompagnamento, così per la singolare, estrosa disposizione nell’afferrare istantaneamente e nello sviluppare ogni combinazione. Lo abbracciai con le lacrime agli occhi e […] gridai che portassero dell’altro champagne, per bere alla salute del grande Italiano, per quanto egli si bagnasse appena le labbra […]. Le sonate Le 37 Sonate M.S.84 e le 5 sonatine M.S.85 rappresentano il corpus più importante tra la produzione di Paganini per chitarra, il cui manoscritto autografo, assieme a moltissima altra musica, ha subito varie vicissitudini e passaggi di proprietà.

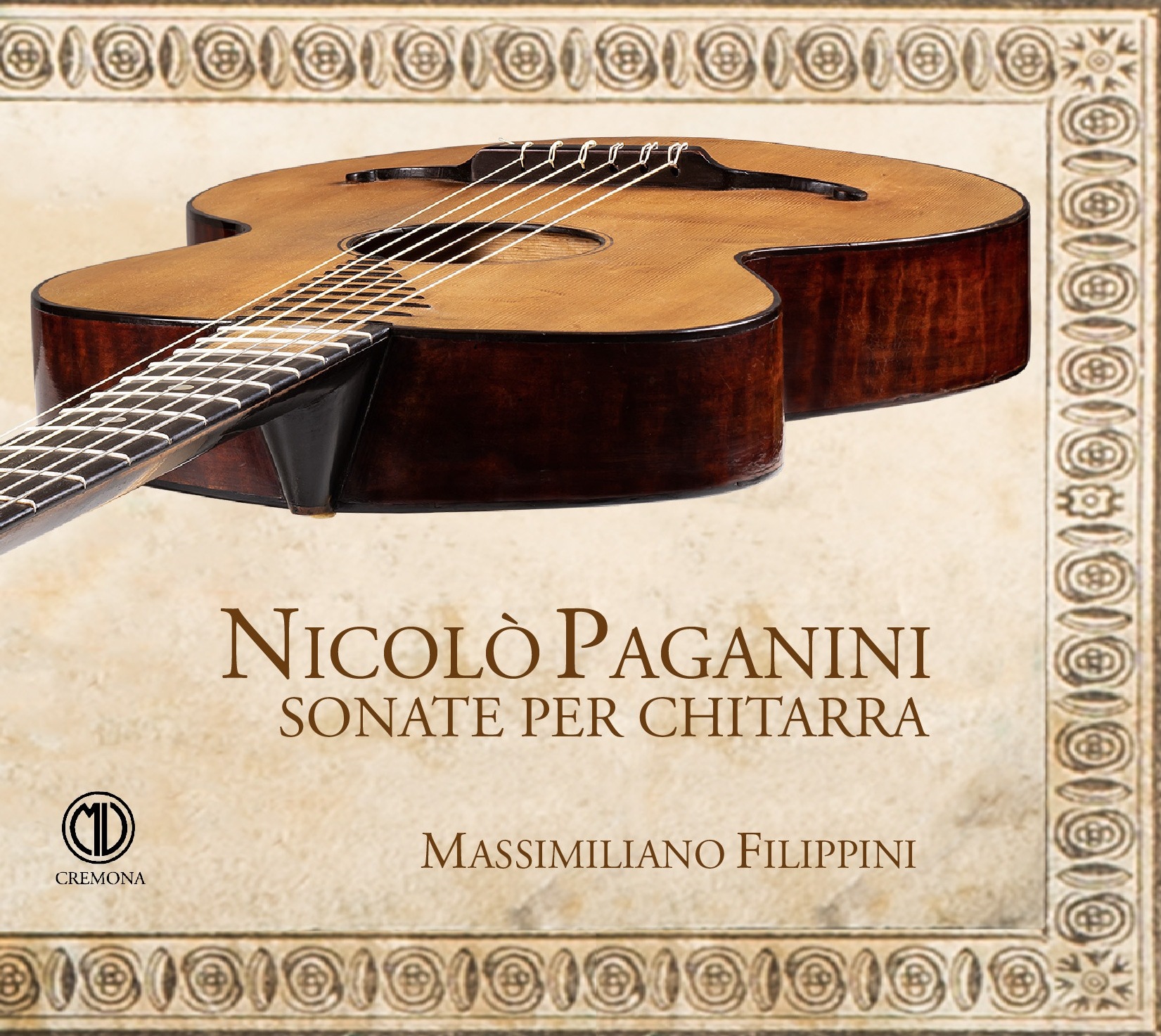

La Chitarra Gaetano Guadagnini Gaetano Guadagnini (Torino, 1796 – ivi, 1852), chiamato nella storiografia della liuteria Gaetano II, era figlio di Carlo e nipote di Giovanni Battista Guadagnini, il capostipite della famosa dinastia di liutai; inizia a lavorare nel 1817 nella bottega di famiglia e presto introduce il suo innovativo modello di chitarra con la cassa più larga rispetto a quello usato dal padre. Il nuovo modello sembra abbia avuto successo tanto che non viene più abbandonato e viene imitato anche da altri liutai. Gaetano costruisce anche violini, viole e violoncelli molto apprezzati. Paganini è un suo contemporaneo ma purtroppo non abbiamo testimonianze di un loro contatto diretto. Però il violinista così scrive all’amico avvocato Luigi Guglielmo Germi il 7 gennaio 1824: Paganini, quindi era a conoscenza di un ottimo artigiano piemontese “eccellente artista per Chitarra”; forse aveva sentito parlare degli ottimi risultati acustici proprio del nuovo modello di chitarra del giovane Gaetano Guadagnini? Non lo sappiamo, però tratta di un’ipotesi suggestiva che va a rendere ancora più coerente la scelta di utilizzare per la registrazione dei brani chitarristici del violinista genovese, una chitarra Guadagnini del 1823, splendido e raro esempio del lavoro di Gaetano II. La tavola armonica è fatta in due pezzi di abete con una venatura di media larghezza; il fondo è fatto in un pezzo di legno di melo, così come le fasce, il manico e la “paletta”; la vernice è di un caldo color rosso-bruno. L’etichetta originale all’interno reca la dicitura “Gaetano Guadagnini fece in Torino nell’anno 1823 dirimpetto a Facaldo. Al secondo piano” e indica che la chitarra è stata costruita nella bottega Guadagnini situata in Contrada della Palma, appena prima del trasferimento dell’attività nel nuovo laboratorio di piazza San Carlo, accanto alla Reale Accademia delle Scienze, che avvenne proprio nell’agosto del 1823. Lo stato di conservazione dello strumento è eccellente in quanto lo strumento non ha mai subito modifiche o riparazioni invasive ma solo semplici manutenzioni; è anche corredata dalla sua caratteristica custodia originale in legno che reca anch’essa il cartiglio originale della bottega Guadagnini. La chitarra faceva parte della collezione privata del maestro Giorgio Ferraris, importante concertista e didatta milanese, insieme ad altri strumenti di grande valore. Le fotografie della chitarra sono riprodotte in alcune pubblicazioni tra cui “La chitarra” di Allorto, Chiesa, Dell’Ara, e Gilardino (EDT/SIdM, 1990) e nel catalogo della mostra “Gli arnesi della musica”, (Rivoli, 2002); è stata usata per concerti e registrazioni sia audio che video da numerosi concertisti tra cui Leopoldo Saracino, Diego Cantalupi e Massimiliano Filippini. |

Paganini and the guitar Niccolò Paganini (Genoa, 1782 - Nice, 1840) is universally renowned as the greatest violin virtuoso of all times and as a huge innovator of violin technique. More recently, experts have focused on the analysis of his numerous compositions in order to contextualize his musical style in the music of his time, and also to reevaluate his persona as composer, since too often this aspect of the artist is overshadowed by his fame as a virtuoso, or hastily confined by the critics as just a medium to show his ability as a player. By analyzing Paganini’s production as a whole, it is clear how assiduous the presence of the guitar is not only as an accompanying instrument in the violin sonatas, in the trios and in the quartets, but also as a soloist instrument. Even the sources reveal that Paganini, besides being an extraordinary and eccentric virtuoso violinist, able to thrill the first half of the 17th century public in Italy and in the rest of Europe, was also a very skilled guitarist, even though his performances with this instrument happened only in private occasions; in fact we don’t have any testimony of public guitar executions. Paganini himself, in his autobiography tells about his relationship with plucked instruments, relationship that started at a very young age:

my father, […]. As a seventeen-year-old I took a trip to northern Italy and to Tuscany, […]. Back in my homeland, I dedicated myself to agriculture, and for and for some years I also enjoyed playing the guitar”. Soon, he starts also composing for this instrument, as he tells to his biographer Maximilian Schottky: “For a rather long period I went back and forth between Parma and Genoa, where I was an amateur much more than I was a virtuoso; in fact I performed a lot, but mostly for private circles. With a lot of diligence I dedicated myself to composition and I wrote much also for the guitar.”

Beginning in the year 1805 Paganini experiences the rise of his carrier as a virtuoso, that will lead him to compose with assiduity pieces of music for violin written to enhance the talent as a player that made him famous; for the guitar, instead, he chooses the accompanying role, as a musician and as a composer. Besides the popular quote by Hector Berlioz which says that “he played the part of the guitar extracting unusual sounds from this instrument” it is again Schottky that declared that “Paganini plays the guitar in an excellent way; he From other sources we have testimonies of Paganini engaged in playing the guitar in occasion of the executions of sonatas and quartets that he composed himself, but always in a private environment. But it is Karol Jozef Lipinski(1790 – 1861), one of the greatest violin virtuosos of the seventeenth century, who made the most vivid portrait of Paganini as a guitarist. Lipinski meets Paganini in Piacenza in 1818, and his narration, besides describing in a very lively way Paganini’s concert that had taken place in the city theatre and the dinner at which Lipinski was invited to attend, is also about their meeting on the following day:

“I invited Paganini to breakfast the next morning. I wanted to play something to him. I also prepared the violin and three solo studies, very difficult and, what is more, in manuscript. I tuned my violin, and he studied one of my studies and tried it over with his fingers on the brim of a glass of champagne which he hardly emptied more than half.”It is not easy”, he said and, hastily making a stand on the table out of a hat and the carafe, he put my music against it. The first part of my study I played better than ever before. I was just preparing myself to repeat it when Paganini, who followed the music with me, jumped up suddenly and without a word ran out of the room. Astounded, and indeed angry, I stood motionless looking at the door which was silently closing. A moment later the maestro came back holding a guitar in his hand. […].Paganini was tuning his guitar. Aghast, I asked him what was the matter. He laughed, sat down near me and begged me to proceed with my study once again, for he wanted to accompany me and thusenrich the art. I was greatly interested, firstly because I did not know that Paganini played the guitar no less enchantingly than the violin and, secondly, I doubted whether he would be able prima vista to find the harmonic basis for my piece. But if on the day before I had admired in him the first violinist of the world, today my admiration knew no bounds in face of his powerful playing on the guitar, his enormous talent enabling him to associate himself with the spirit of my work and to create a miraculous accompaniment, and still more in face of the unaccountable quickness, amounting to inspiration, with which he grasped every harmonic combination. With tears in my eyes I embraced him, and then I called on a servant to bring another bottle of champagne to dof the great Italian, although he himself drank very little.”

The sonatas

The 37 Sonatas M.S.84 and the 5 Sonatinas M.S.85 compose the most relevant corpus of Paganini’s guitar production, and their hand-written score, together with many other pieces of music, underwent various vicissitudes and transfers of ownership. At the beginning of the 20th century it was part of a private collection, but in 1925 Zimmerman, an editor from Frankfurt Am Main, published a selection of 26 pieces, rendering for the first time accessible to the public the Genoese violinist’s pieces for guitar. However the pieces were chosen by the editor without taking into account the movement’s belonging to a specific sonata, and they were presented as small free pieces. The acquisition of the Paganini’s manuscript by the Italian State in 1972 and its safekeeping at the Biblioteca Casanatense in Rome allowed the study of these pieces, enabling the scholar Danilo Prefumo to reassemble the puzzle, showing the organicity of the collection composed by the 37 Sonatas M.S. 84, that, except for the last four, all are in two movements. The first movement is always constituted by a Minuet in 3/4 , while for the second movement we have pieces named Allegretto, Rondoncino or Valtz. The way the manuscripts appear suggests the idea that they were intended for private use: they are in fact without a title page, and are full of erasure and various scribbles. Many passaggi di bravura stand out in these sonatas, where brilliant technical solutions are often exerted. The scholar Eduardo Fernandez states that the pieces are organized according to the criteria of increasing difficulty, starting with a basic level in the first sonata and reaching the highest degree of difficulty in the last one. Indeed the Sonata no.37 is remarkable because of a long passage of fast and acute triplets which are very difficult to execute, but in the collection it is possible to find also other ones of considerable difficulty already in the no. 18 and in the no. 20, that could also exceed in difficulty compared to the following ones. All the sonatas are in major key, except for the no. 33 that is in C minor. No. 28 presents the employ of the detuning “in viola d’amore”, which consists in lowering the sixth string from E to D, the fifth string for A to G and the first string from E to D, making a peculiar sound. The Sonatinas M.S. 85 and the sonata M.S. 87, differ from the other sonatas due to their greater breadth and formal construction. They are all in two movements, except for the first, the third and the fourth one, which is compounded just by one ample movement in sonata formwith two themes. The second sonata presents the detuning of the sixth string from E to C. What brings the sonatas and the sonatinas together, besides the keen sense of melody, is the virtuosity of some technical solutions: these were already used by other guitar composers, but Paganini elevated them to the greatest level ofgenius and fantasy.

The Gaetano Guadagnini guitar Gaetano Guadagnini (Turin, 1796 – ivi, 1852), called Gaetano II in the historiography of violin making, was Carlo’s son and Giovanni Battista Guadagnini’s nephew, the latter being the progenitor of the famous dynasty of luthiers; he starts working in the family shop in 1817, and he introduces soon his innovative model of a guitar made with a larger corpus compared to the ones his father used to make. This new model was successful, in fact it was never substituted and it was soon imitated by other luthiers. Gaetano also made violins, violas and cellos which were very appreciated. Paganini lived in the same period Gaetano did, but unfortunately we have no testimony of a direct contact between the two of them. Nonetheless the violinist wrote these words to his friend Luigi Guglielmo Germi, an attorney, in January 7th 1824: “I’m writing to you because a lady is looking for a beautiful, but most importantly, fine guitar, if she finds it here let me know, otherwise ask my brother, meaning to demand him to inquire from my copyist where or in which village of Piemonte lives that fellow whose name I don’t recall, but who is an excellent artist for guitars, and commission him a good instrument, well refined and well sounding. Please take care of this.” Therefore Paganini knew about a great Piedmontese artisan, an “excellent artist for guitar”; he perhaps heard about the fantastic acoustic results of the new model of guitar made by the young Gaetano Guadagnini? We don’t know, but this is a suggestive hypothesis that makes even more coherent his choice of using an instrument by Guadagnini of the year 1823, a splendid and rare artwork of Gaetano II, to record the Genoese violinist’s pieces for guitar. The soundboard is made of two pieces of spruce with grain of medium width; the back is made of a single piece of apple wood, so as are the ribs, the neck and the palette; the varnish is of a warm red-brown color. The original label states “Gaetano Guadagnini made this in Turin in 1823, front neighbor of Facaldo. Al the second floor” and shows that this guitar was built in Guadagnini’s shop, located in Contradadella Palma, right before the business was moved to the new atelier in piazza San Carlo, right next to the Royal Academy of Science, in August 1823. The state of conservation of the instrument is excellent, since it has never been subjected to modifications or invasive repairs, but only to modest maintenance interventions; it is also accompanied by its characteristic original wooden case, which displays, as does the instrument, the original cartouche of Guadagnini’s shop. The guitar was part of the collection of Maestro Giorgio Ferraris, an important Milanese concertist and pedagogue, together with other instruments of great value. Images of the guitar are reproduced in publications such as “The guitar” by Allorto, Chiesa, Dell’Ara, and Gilardino (EDT/SIdM, 1990) and in the catalogue of the exhibition “The tools of music”, (Rivoli, 2002); it was also used for concerts and both audio and video recordings by multiple concert artists, among the many we quote Leopoldo Saracino, Diego Cantalupi and Massimiliano Filippini. |

|